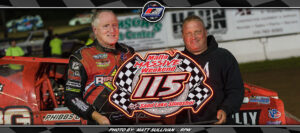

Story By BUFFY SWANSON / NORTHEAST DIRT MODIFIED HALL OF FAME – WEEDSPORT, NY – Continuing his family’s legacy, “The Pocket Rocket,” Danny O’Brien from Kingston, ONT, has been chosen as a 2023 inductee into the Northeast Dirt Modified Hall of Fame.

Driver inductions and special award ceremonies are scheduled for Thursday, July 13 at the Hall of Fame Museum on the grounds of Weedsport Speedway in New York.

Patriarch Pat O’Brien Sr. put his name in the record books at the old Watertown and Kingston speedways, back in the 1950s and ’60s.

“He raced for 18 years—his last year was 1974, I believe. I was very young. Then he got out of racing to grow the family business, Pat’s Radiator,” Danny detailed. “Years after, he took Pat and I to Brockville and Cornwall a few times. He kinda got the itch and gave us a hand to get started. That’s where all this came from.”

Three years older, Pat Jr. began racing in 1985, with middle brother Danny turning wrenches in the pits. That lasted two years before Danny surfaced from the sidelines to grab his own seat.

“I started right in 358 Modifieds. In fact, I’ve never raced a Sportsman car! And I ended up winning three races that first year—one race at Brockville, and then in late July or early August we won two in a row down at Cornwall,” O’Brien recalled his dynamic debut in the headlining division.

By the early ’90s, Danny was full in, racing Edelweiss on Thursday nights, Brockville Friday, Can-Am on Saturdays and Cornwall on Sundays—all while holding down a full-time job at the family business.

“I did everything with my own car, except for the Gallo brothers at Fonda. I had a couple years with the Evoys, ran the Kendrick Global Warranty 7* in 2009-10 and for Paul and Heather Topping in 2018, then filled in a little bit for the Slacks,” O’Brien said. “Other than that, most of it has been in my own equipment.”

More aggressive than his even-keeled brother Pat, O’Brien just about willed himself into the winner’s circle. Currently credited with 225 career wins at 11 tracks in two countries, Danny was the 1994 DIRT big-block champion at Cornwall, where he also won four 358 titles; a four-timer in Brockville’s Ogilvie’s 358 Modified Triple Crown Series; a two-time winner of both the Doiron Engineering Cup at Cornwall and Mohawk’s Memorial Cup Series; and the 2005 Lucas Oil Canadian Dirt Series champ.

At Brockville, he’s been close to unbeatable, banking 14 track titles and 99 victories, the all-time record.

Of course, at most of these meets, Danny’s primary rival would be…his brother Pat.

“At Brockville and Cornwall, it would be a slugfest between the two of us for wins on many nights. You’d lose ’em with one or two to go or win ’em with one or two to go. There were so many nights we finished one-two together,” O’Brien described their weekly tug-of-war, which got heated at times. “In the 2000s, my brother Timmy was racing with us also—and we had a couple of one-two-three podium finishes at Brockville. That was pretty cool.”

In his autobiography, legendary driver Bob McCreadie gave this succinct synopsis of the two eldest O’Brien brothers: “Pat is the better driver—but Danny wants it more.”

And all of Danny’s intense, single-minded determination was put to the ultimate test in 1996. At Can-Am on Labor Day weekend, he got caught up in a hellish and heart-stopping wreck that ripped the cage right off his car and, even more alarmingly, sent his helmet skidding down the track.

Dead silence. Every spectator on the premises that awful day was convinced they had witnessed a fatality. “Unsurvivable,” they said.

But O’Brien is made of tough stuff. He miraculously lived—made it through the accident, made it through all the excruciating surgeries to save his eyesight and reconstruct his face. (see sidebar)

And he never lost his focus or desire.

The following April, he was back in the driver’s seat; within a month, he was back in victory lane. Right where he left off.

“I slowed down probably around 2015-16. And at the end of 2018, I stepped out. It was very hard to get funding, to keep it all going. It got to be another full-time job along with the business,” Danny admitted.

“And the main reason is…I wanted to win so bad that I was spending every night in my garage, to make sure nothing broke. I was obsessed with it. It got to the point where I got burned out and wanted a break.”

It was a fairly short retirement.

“Bob Slack called me on a Friday morning in late August in 2021. Casual conversation. ‘You feeling good? You want to go racing?’ And that was it,” O’Brien related. “His son Dalton wanted a break, and he needed someone to fill in for a little bit.”

Both Dalton and Tim Fuller recommended Danny as the temporary replacement.

It was more of a transition than O’Brien had expected. “That was tough: when I quit we were running torsion-bar suspensions. So I came back to basically a whole new race car, on coils. It took a few weeks to figure it out.”

Not to worry: Danny showed well in the season-end shows, winning the big Applefest Shootout at Brighton.

Forgoing a full-time commitment, O’Brien stayed on as a part-timer with the Slack team, splitting up a schedule with Tim Fuller and Erick Rudolph until Dalton’s return at the end of 2022.

“Then two weeks after the Fall Nationals race at Brockville, Steve Polite called me. It took a bit of convincing—I didn’t say yes right away. But he made me a lucrative offer, they’re really great people, been racing in the Brockville area for years, and I agreed to give it a shot. As of right now, we’re at 10 races this year and we’ll see where it goes.”

The carrot dangling in front of Danny? His 100th career win at Brockville.

And he is hell-bent to get it. “I’m going to work hard to learn this new Bicknell car this winter, really understand it. And we’re gonna come out swinging!” O’Brien promised. “I’m more excited than I have been in years. I want to get this 100th win—very, very badly.

“I have no interest in going out there and racing for fifth.”

Looking back on a Hall of Fame career, Danny most values the opportunity to race against—and learn from—some of the titans on the tour.

“I think ’95 was probably our best year—I believe we had 15 or 16 wins that year. Everything was clicking, it didn’t really matter where we went. We were just fast!

That was in my own car, too,” he pointed out.

The pinnacle that season: beating Frank Cozze, Buzzie Reutimann, Doug Hoffman and Danny Johnson to the line to take the Super DIRT Series big-block event at one of his home tracks, Can-Am, in August.

“That was really cool! All the guys were there, and it was really tough to win one back then,” O’Brien said of the talent pool on the DIRT tour.

Many of those top drivers were generous with their knowledge—and a kid like O’Brien took it all to heart. “Jack Johnson used to help me at Fonda. Joe Plazek. All those guys would get you guided in the right direction and give you help any time they could,” he acknowledged. “At the time, I figured they wanted to keep you straight and up to speed so you wouldn’t cause trouble.

“Bob McCreadie was always a big help in my career. You could always go sit down with him, ask a question and he’d give you a straight answer,” Danny maintained.

“At the end of the day, it all made the racing better.”

NE Dirt Mod Hall of Fame Inducts Pioneer Driver Bob Cameron

NASCAR’s 1949 New York State champion Bob Cameron, a barnstorming trailblazer in the sport’s infancy, will be honored as a 2023 inductee into the Northeast Dirt Modified Hall of Fame. Driver inductions and special award ceremonies are scheduled for Thursday, July 13, at the Hall of Fame Museum on the grounds of Weedsport Speedway in New York. The event is free and open to the public.

Back in that post-war period it was the wild, wild west—Western New York, that is, where it all started for Cameron. The scrappy renegade, from the Buffalo suburb of Kenmore, came up quick: driving for anyone and everyone, ransacking race tracks up and down the East Coast, taking no prisoners. He was nothing short of spectacular at Buffalo’s Civic Stadium where SRO crowds topping 20,000 went wild as he willfully racked ’em up—21 checkereds in 24 starts, one season, always starting far back in the field and bulling his way through wreck-infested features. At county fairgrounds in Monroe, Chautauqua, Livingston, Cortland, Genesee, Vernon, Afton, Naples and Jamestown; on both dirt and asphalt at Brewerton; and later, on the blacktop at Spencer and Oswego—Bob staked his claim.

And took no guff. Hal Lawrence—who raced and traveled with Bob, and worked with him in the circulation department of the Buffalo Courier Express—remembers just how intimidating he could be.

“We were racing at Civic Stadium, probably ’54-55. Bobby and Gordie Reed were battling it out in a heat race. Mr. Reed was continually bumping Bobby, trying to get by him, and finally put him in the wall. In the pits after, there was a confrontation, a shouting match. Everybody knew Bobby was very aggressive so they surrounded him and grabbed him, while he was yelling at this Gordie Reed. He looked at the two guys who were holding his arms and swore, ‘Lemme go! Lemme go! I’m not gonna hit him!’

“And just like John Wayne—when they let him go, he said, ‘The hell I ain’t!’ Boom! Knocked Gordie Reed flat! They dragged him away,” Lawrence recalled. “But that was Bobby Cameron. And when it was over, it was over.”

Cameron was never one to back down from a fight. Protesting the pay structure and lack of safety protocol under promoter Ed Otto, Bob and fellow Buffalo racers joined forces to form a union in 1950 and organized a highly-publicized strike outside Civic Stadium. That pushback put a target on Cameron’s back—with NASCAR taking aim.

A stint in the U.S. Army starting in ’51 saw him stationed near Baltimore, eyeing the area racing scene. He wrangled permission to compete as many as four nights a week, under an assumed name: Bob Carran.

Famed engine builder Bob Wallace, who had moved to the Baltimore area from upstate New York and formed a partnership with Delaware race track magnate Melvin Joseph, told the following story in Bob Weigman’s book, “There Used to Be a Speedway.”

“I had a boy that I had picked up for a driver who was stationed at Edgewood. Bobby Cameron. And he was blackballed from NASCAR just like I was. He led a strike against Ed Otto in Buffalo, so they blackballed the leaders of the strike,” Wallace narrated.

“I found out through the grapevine that this kid was as sharp as a razor in a race car. And we went to Westport one night; got there a little bit late, intentionally. Bobby went out there, went around that track and he beat Johnny Roberts and all the hot-shots. It was the Mid-Summer Night Championship. And they took a picture of him standing by the race car, and sent it up to Ed Otto in New York.

“The secret was out.”

Otto had a hand in Westport as well, and was irate, immediately grabbing the phone to read promoter Bill Heiserman the riot act. “You just made Bobby Cameron the champion of your Mid-Summer Night Championship!” bellowed Otto.

“The next week we tried to pull in late like we did the week before and Heiserman was waitin’ at the gate. He said, ‘You bastards won’t get away with that this week!’” Wallace told.

But they got the last laugh: “We went there three other times, with Cameron driving. But we put a mustache on him and blackened his eyebrows. We’d paint that car—change the whole color of it and the number on it. And we did that three times in a row. Won three times in a row,” Bob boasted.

“Roberts, Schneider, everybody was there! Of course, my car ran good, too,” Wallace assured. “But it was Bobby’s wizardry with the steering wheel that won. He was magic in a race car!”

His military time served, Cameron came home to find that the climate had barely altered.

“Safety was a big concern—with the Ed Otto circus atmosphere, if a car spun out or crashed or had a problem, they would just continue to race. There was no such thing as a caution flag, you didn’t stop the race for anything,” Hal Lawrence reported. “And some drivers got severely hurt. I recall a fellow by the name of Eddie Trojner, rolled over and his seat belts were over the seat, rather than strapping him in tight. And when he went over he slid out and hurt his back. They left him like that in the car until the end of the race. He never walked again…

“That was just an example of how it was—you spin out today, everything stops. It didn’t happen back then. The starter tried to look out for the drivers, but he was under pressure to just keep it going because it was more exciting for the crowd.”

As Cameron bitterly complained to Lawrence on the ride home from a big event at the Syracuse mile—a race in which Bill Wimble caught a tail-ender and rolled, with no safety equipment in sight: “They don’t really give a damn about the drivers! It’s all about the money.”

So he decided to make a difference. In 1956, Bob cut back his seat time and signed on as a NASCAR Safety Inspector at Civic Stadium, vowing to “see to it that all preventable injuries are avoided. Checking the safety equipment on all the cars is the first step toward curbing fatalities in racing.”

Despite Cameron’s solemn commitment to keeping the sport safe, unfortunately he couldn’t control every aspect. In the ultimate irony, through no fault of his own, Bobby Cameron lost his life in a fiery and senseless wreck during warmups at Lancaster Speedway on June 4, 1960. He was only 36 years old.

Yet, the Cameron legend lives on—more than 60 years later.

Motorsports historian Larry Jendras recalls a humorous exchange at a Maryland Oldtimers of Racing get-together, some years back. “I brought about 20 books of old photos for the guests to look at,” Jendras said. In one was a picture of Bobby “Carran,” behind the wheel of George Heffner’s No. 88 1937 Ford coupe at Old Dominion in 1954. “I took the book over to George’s table and asked him who was in the 88 in that photo. I clearly knew it was not one of his usual drivers—Ken Marriott, Ralph Smith or Ed Lindsay.”

In a booming voice, Heffner announced, “Well, that is the best driver I ever had in one of my cars, Bobby Carran!”

Jendras laughed. “Now, this was within earshot of Ralph Smith, who many consider George’s best driver—Ralph won the 1955 NY State Fairgrounds race in Heffner’s 88.

“George was just razzing his old drivers,” Larry explained. “But he said he really would have liked Bob to stay in Maryland.”

Thanks to racing historians Tom Schmeh and Larry Jendras for extensive source material.